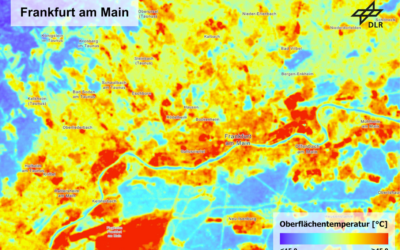

Over the last 12 years, our team at the Earth Observation Center (EOC) of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and our Earth Observation Research Cluster at the University of Würzburg in close collaboration with many researchers across the globe has produced various scientific papers documenting and analyzing different aspects of this highly dynamic urbanization process in China using remote sensing and other geodata. We take the publication of a new paper on this subject in the journal Nature Cities from yesterday (https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-024-00177-8) as an opportunity to briefly review these various research studies:

We have documented that China’s megacities are among the fastest growing megacities in the world: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0034425711003427. And, we measured that nowhere in the world urban growth rates have been higher than in East Asia: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275124003317.

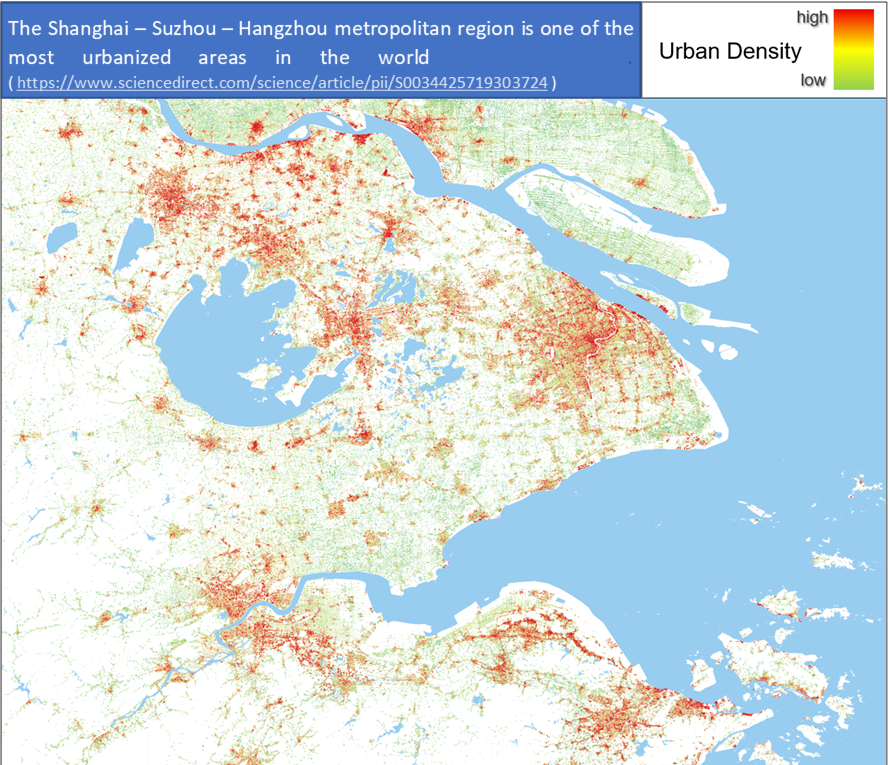

We were able to show how the Pearl River Delta has developed into a huge, interconnected urban landscape (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622813002786) and that this urban agglomeration is today the largest city in the world: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0034425719303724. We were able to show that urban expansion was not evenly distributed across China and also varied over time: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17538947.2017.1400599. We analyzed to what extent the spatial hierarchical urban system in China corresponds to the Central Place Theory: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197397519307489.

The high dynamics of urbanization often mean that there is not enough living space in cities, resulting in informal settlements and the development of special forms of housing. In China, for example, these are so-called urban villages: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622817309955.

However, there is another phenomenon that accompanies the high dynamics of urbanization in China, so-called ‘ghost cities’. It may sound surprising, but despite the high level of urbanization dynamics, there has been an overproduction of housing. Inspired by a visit to the ghost city of Lingang – a city built for around 800,000 people and virtually empty at the time of our visit https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-44841-0_25 – we took a closer look at this phenomenon:

Using satellite data, we detected ghost areas that allow – based on our assessments – to house at the absolute minimum 13.6 million more people in the cities across China: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204619314185 and https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10144205. The ghost areas have very different geographic locations and intra-urban spatial patterns: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/23998083221092775?journalCode=epbb.

However, ghost cities are only an extreme. Much more common are cities that are not completely uninhabited, but whose capacity is far from being fully utilized: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0198971519300833. A concept termed ‘underload city’ has been introduced to define cities carrying fewer people and lower economic strength than their land carrying capacity: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42949-022-00057-x. For the city of Guiyang an average housing vacancy rate has been estimated at 25%: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204622000809

The latest paper published in the journal Nature Cities reveals housing utilization efficiencies across China are low and even decreasing in the decade from 2010 until 2020: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-024-00177-8 and https://communities.springernature.com/posts/the-decreasing-housing-utilization-efficiency-in-china-s-cities.

We thank all colleagues for the inspiring collaborations over the years and we are very much looking forward to future joint research work.

|

© Pictures Dr. Lifeng Shi, used by permission